Understanding how much weight a child truly bears in a standing frame is key to making informed clinical decisions. Whether the goal is bone health, joint alignment, or postural control, the angle of the standing frame makes a measurable difference – but perhaps not in the way many assume. This blog reviews the physics behind weight bearing in standing frames, explains how gravity and angle interact, and highlights what this means for safe, effective standing therapy.

How Does Recline Affect Load?

Clinicians regularly ask, "If a child can't stand fully upright, are they still getting meaningful weight-bearing benefits?" The answer is a reassuring yes. Even at 30° off upright, children are still taking around 85-90% of their body weight through their feet. And the reason why comes down to something you learned at school and probably thought you'd never need to remember: trigonometry.

Gravity Doesn't Change, But the Direction Does

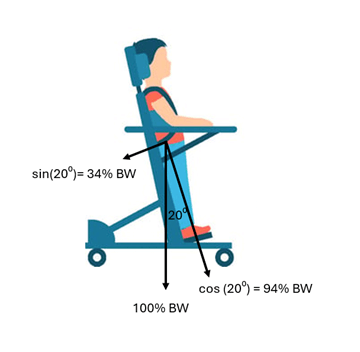

When a child stands completely upright, their entire body weight (BW) travels vertically down through their skeleton and into the footplates. 100% of body weight supports bone health, muscle stretch, and alignment. However, when the frame is reclined, what changes is how that downward force is shared between the different supports. Body weight is then split between:

- A component pushing straight down through the feet

- A component pushing into the support pads (head, chest, pelvis, knee, heels)

The "Magic" of Trigonometry

Using trigonometry, we can work out how much of the body's weight still acts through the feet as the frame tilts.

- Load through the feet = BW x cos (angle from upright)

- Load through the support pads = BW x sin (angle from upright)

These two forces always mathematically combine to balance the same 100% body weight – but they act in perpendicular directions.

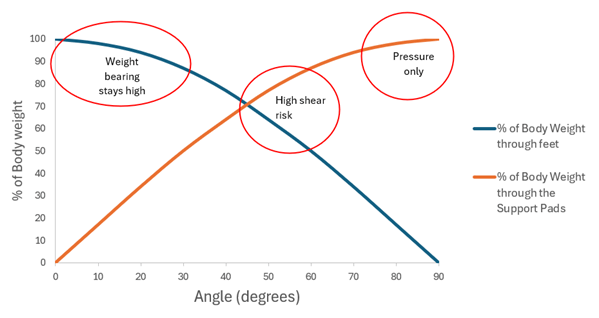

So even if a child is positioned 20° off upright, approximately 95% of their body weight still travels through their feet and skeleton. That's a meaningful load for stimulating bone density, proprioception, and postural activity. Here's what that looks like to different angles of recline:

| Angle from upright |

% of BW through feet |

% of BW through the back pads |

Clinical interpretation |

Shear risk |

| 0° |

100% |

0% |

Full weight bearing through feet |

Low |

| 10° |

98% |

17% |

Almost upright |

Low |

| 20° |

94% |

34% |

Mild recline |

Low-moderate |

| 30° |

87% |

50% |

Partial support on pads |

Low-moderate |

| 40° |

77% |

64% |

Shared load |

High |

| 50° |

64% |

77% |

Shared load |

Very high |

| 60° |

50% |

87% |

Shared load; sliding risk |

High |

| 70° |

34% |

94% |

Mostly supported by pads |

Moderate |

| 80° |

17% |

98% |

Nearly lying back |

Pressure mostly |

| 90° |

0% |

100% |

Fully supporting in horizontal |

Pressure only |

Why Shear Peaks Around 45-60° from Upright

Shear is the force that acts parallel to the skin or body surface, causing layers of tissue to slide against each other. Shear is something to be avoided. It is directly proportional to the perpendicular load onto the pads. In a standing frame, shear occurs when gravity tries to make the child's body slide down the back pads, while the pads resist that motion through friction and support straps.

When Is Shear Risk Highest?

Shear is greatest when the child's weight is shared between the feet & the pads and gravity is pulling strongly both downward and along the surface of the pad. So, at 30° the shear may be moderate, but the risk is low-moderate because there is less weight through the pads. But at approximately 45-60° recline, where both supports are taking substantial load and the body is trying to slide down, the risk is greater. Beyond 70° most of the load presses into the pads rather than along them, so shear risk drops quickly.

Clinical Takeaways

- Even when children stand in partial recline, meaningful weigh bearing continues. For example, about 85% of body weight will still transfer through the lower limbs and feet at 30° recline.

- Peak shear risk occurs between 45° and 60° recline when both feet and pads share the load. Ensure the pads are cushioned and positioned to spread the pressure. As you move closer to horizontal, both shear forces and risk fall.

- Small position changes or adjustments to the cline angle can relieve prolonged shear and improve standing tolerance.

Summary

Even when a child isn't fully upright, most of their body weight still travels through their feet and skeleton – thanks to trigonometry!

Laura Finney has more than 20 years of experience in pediatric disability. After gaining a Master's and PhD in Clinical Engineering from Strathclyde University, she pursued a clinical career in the NHS as a Clinical Scientist specializing in adaptive equipment provision for children. Laura now enjoys the dual world of product development and pediatric therapy.

Laura's passion is in applying a biomechanical approach to the problem-solving of human-product interfaces with the ultimate goal of encouraging movement and restoring natural function.